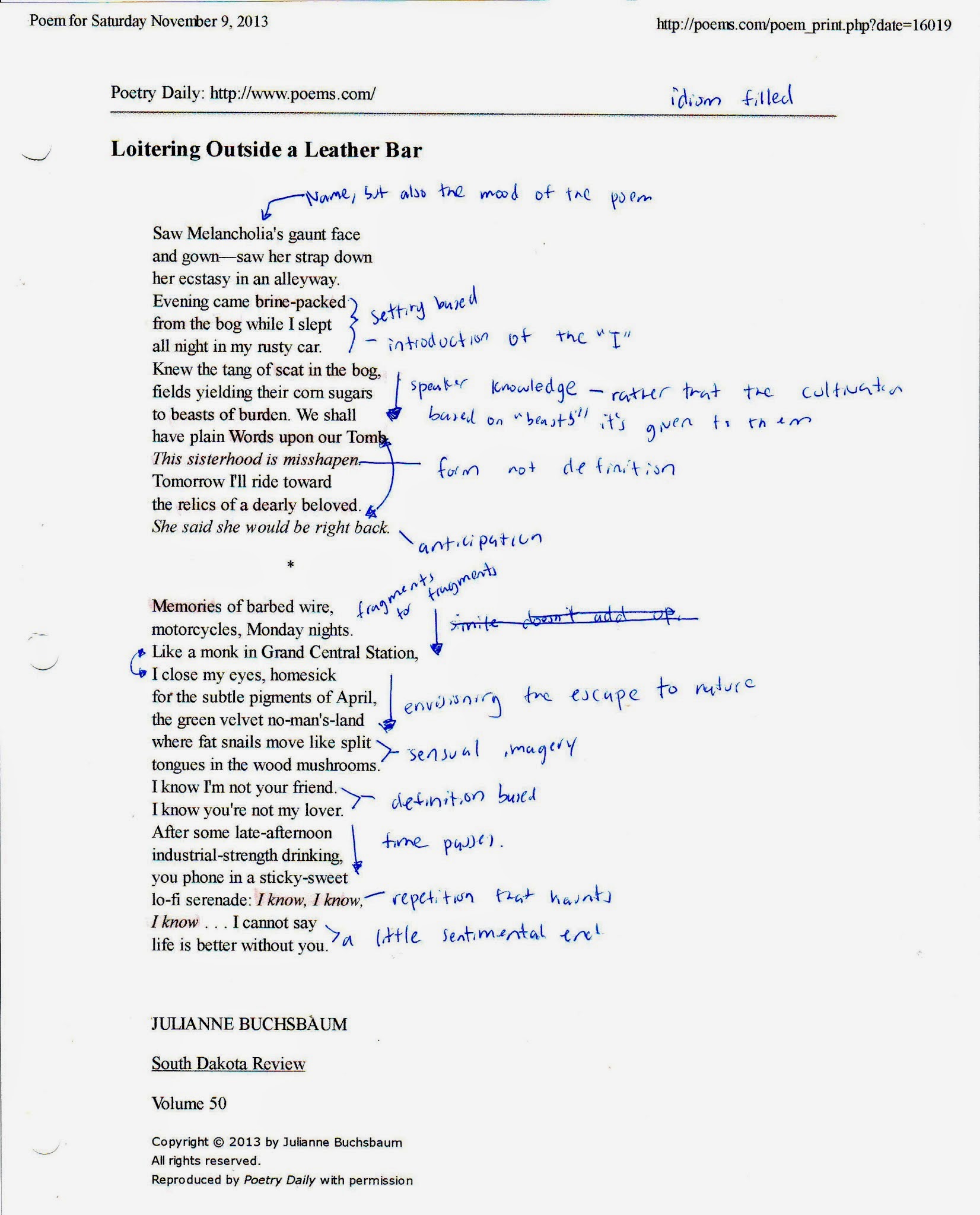

Original poem reprinted online here: "Loitering Outside a Leather Bar" by Julianne Buchsbaum

Originally read: November 12, 2013

More information about the Poet: Julianne Buchsbaum

The scene versus the individual. I'm not talking about setting when I mention the "scene," I feel this poem depicts the mood, the area, the type of situation one would find in "her strap down / her ecstasy in an alleyway." This sort of seedy underground scene without over-dramatizing.

But first the poem starts with an observational verb, "Saw Melancholia's gaunt face / and gown" Yes, Melancholia is a pun and foreshadow of melancholy, but note how this line sets up an away from what is "real." I know I stated that this poem depicts the mood and situation really well, and it's because of the name. Academically read, this poem has allusions. But, unless you've been there, people are named Melancholia. I'm just stating that, to me, that suspension of disbelief is still intact.

The poem then goes to the speaker with, "Evening came brine-packed / from the bog while I slept / all night in my rusty car." This is a very concrete personal line. Then comes a more metaphorical line, "Knew the tang of scat in bog, / fields yielding their corn sugars / to beasts of burden." Name, yes that adds to the scene, but this line adds to the mindset of speaker who waits in the car and is now thinking further and further away.

"Words upon our Tomb / This sisterhood is misshapen." Past me wrote, "form not definition" -- note the eulagaic effect happening in the mind -- something is over beofre it started, "She said she would be right back"

The break here (along with the asterisk between them) feels more like a separation of ideals but with conditions. What the asterisk does is connect these two stanzas together -- not by words, but by symbol.

"Memories of barbed wire, / morocyclists, Monday nights." Concrete once again, "Like a monk in Grand Central Station, / I close my eyes, homesick." What throws me off here is the simile of the monk which deeply contrasts the first stanza, but what ties it all together is what the monk represents -- someone who is away and searching. The poem goes further into nature though which feels off, "the green velvet no-man's-land / where fat snails move like split / tongues in the wood mushrooms." And okay I'm losing my suspension of disbelief and the poem becomes more symbolic than a scene.

But then come the direct lines, "I know I'm not your friend. / I know you're not my lover." A confession in a sense, no more of a confirmation about a relationship status in which the speaker is talking to himself/herself(?)

Okay, so at this point I have a feeling the speaker is a woman because sisterhood, but nothing is really stated here like the relationship --- the only thing concrete is the scene, "I know, I know, / I know . . . I cannot say / life is better without you."

So here's the leap, the thing that the speaker is missing is not the person, but the entire scene. Note how there's the focus on the car and staying, and then the simile of the "Grand Central Station" and the monk missing home happens in the second part.

Admitting what the speaker is not pushes the momentum of letting go, but not by choice, by realization. So when we get to the end the use of sentimental language seems to be unfocused.

Originally read: November 12, 2013

More information about the Poet: Julianne Buchsbaum

The scene versus the individual. I'm not talking about setting when I mention the "scene," I feel this poem depicts the mood, the area, the type of situation one would find in "her strap down / her ecstasy in an alleyway." This sort of seedy underground scene without over-dramatizing.

But first the poem starts with an observational verb, "Saw Melancholia's gaunt face / and gown" Yes, Melancholia is a pun and foreshadow of melancholy, but note how this line sets up an away from what is "real." I know I stated that this poem depicts the mood and situation really well, and it's because of the name. Academically read, this poem has allusions. But, unless you've been there, people are named Melancholia. I'm just stating that, to me, that suspension of disbelief is still intact.

The poem then goes to the speaker with, "Evening came brine-packed / from the bog while I slept / all night in my rusty car." This is a very concrete personal line. Then comes a more metaphorical line, "Knew the tang of scat in bog, / fields yielding their corn sugars / to beasts of burden." Name, yes that adds to the scene, but this line adds to the mindset of speaker who waits in the car and is now thinking further and further away.

"Words upon our Tomb / This sisterhood is misshapen." Past me wrote, "form not definition" -- note the eulagaic effect happening in the mind -- something is over beofre it started, "She said she would be right back"

The break here (along with the asterisk between them) feels more like a separation of ideals but with conditions. What the asterisk does is connect these two stanzas together -- not by words, but by symbol.

"Memories of barbed wire, / morocyclists, Monday nights." Concrete once again, "Like a monk in Grand Central Station, / I close my eyes, homesick." What throws me off here is the simile of the monk which deeply contrasts the first stanza, but what ties it all together is what the monk represents -- someone who is away and searching. The poem goes further into nature though which feels off, "the green velvet no-man's-land / where fat snails move like split / tongues in the wood mushrooms." And okay I'm losing my suspension of disbelief and the poem becomes more symbolic than a scene.

But then come the direct lines, "I know I'm not your friend. / I know you're not my lover." A confession in a sense, no more of a confirmation about a relationship status in which the speaker is talking to himself/herself(?)

Okay, so at this point I have a feeling the speaker is a woman because sisterhood, but nothing is really stated here like the relationship --- the only thing concrete is the scene, "I know, I know, / I know . . . I cannot say / life is better without you."

So here's the leap, the thing that the speaker is missing is not the person, but the entire scene. Note how there's the focus on the car and staying, and then the simile of the "Grand Central Station" and the monk missing home happens in the second part.

Admitting what the speaker is not pushes the momentum of letting go, but not by choice, by realization. So when we get to the end the use of sentimental language seems to be unfocused.

Comments

Post a Comment