Original poem reprinted online here: "Skunk Hour" by Robert Lowell

Originally read: September 19, 2013

More information about the Poet: Robert Lowell

Probably the most influential poem in the mid twentieth century. Overstatement, probably (I don't know the entire history of late 1950's - 1970's poetry -- well there's "Howl" which played more of a cultural impact...,but let me just continue). Most influential in that this style of writing, Confessionalism, was recognized by critics and academia which, in turn, opened up recognition of other poetry styles.

So this is why many students have to (begrudgingly) write essays about this poem specifically. And let's be honest, this poem is the anti-fun at least for the first half, and then confusing but momentum based in the last half. Yes, I wrote probably five essays on this poem during my academic career (all of paling in comparison with the five thousand other essays about this poem), and here is another one.

The one thing I note in the first half of the poem is the setting and location: somewhere in the north east, and sometime past summer. What the poem does in the beginning is start out in a third person mode -- more observation based, and more exposition based. There are three characters described in the first half: an heiress, a "summer millionaire," and a "fairy."

So the first is the heiress, "Nautilus Islands' hermit" who "lives through winter in her Spartan cottage;" note the semi-colon here to act an immediate comparison here, "her sheep still graze above the sea." Note how the sheep acts like a metaphor of distinction. Not drowning, but still "above all things" and yett, "she's in her dotage." Someone living alone.

So the following line sums up the first stanza, "Thirsting for / the hierarchic privacy / of Queen Victoria's century," the importance here is not the verb (thirst) but the time frame (Queen Victoria's century) and how privacy can be looked at as escapism.

The next three lines have a slight rhyme scheme, "she buys up all / the eyesores facing her shore, / and lets them fall" with "all" and "fall" -- this sense of a descent is on the surface, but the rhyme is also foreshadows the next person discussed, "the summer millionaire." (note the usage double -ll with the next stanza).

"The season's ill-- / we've lost our summer millionaire / who seemed to leap from an L.L. Bean" Yes, the last word is "catalogue" but I didn't want to exapnd my quotes. "Ill," "millionaire" and "L.L. Bean" all have the double -ll in it. Why? I don't know, but to me, this is the last vestige of hanging on to something similar -- even if it's the same letter drowned out sonically within itself. And of course the visual language shows a certain type person being described, "his nine-knot yawl / was auctioned off to lobstermen. / A red fox stain covers Blue Hill." -- what's left behind is picked up back someone lower (lobstermen).

The last description is toward "our fairy." Yes, the fairy could hit multiple references: a gay man, a whimsical person, or a figment (all can apply here) I think this stanza opens up for several types of criticism to be applied (Colonialism, Historicism, Deconstruction) -- whatever floats your boat. Just note that the focus of color "orange," " his fishnet's filled with orange cork, / orange, his cobbler's bench and awl;" bright, somewhat apparent colors, which hides intent, "there is no money in his work, / he'd rather marry."

This is the first half of the poem: people who are lost from the iconic to the prestigious to the lowly to the bright -- all of them lost internally in someway, but are remembered and are known externally. This concept will apply to the second half of the poem.

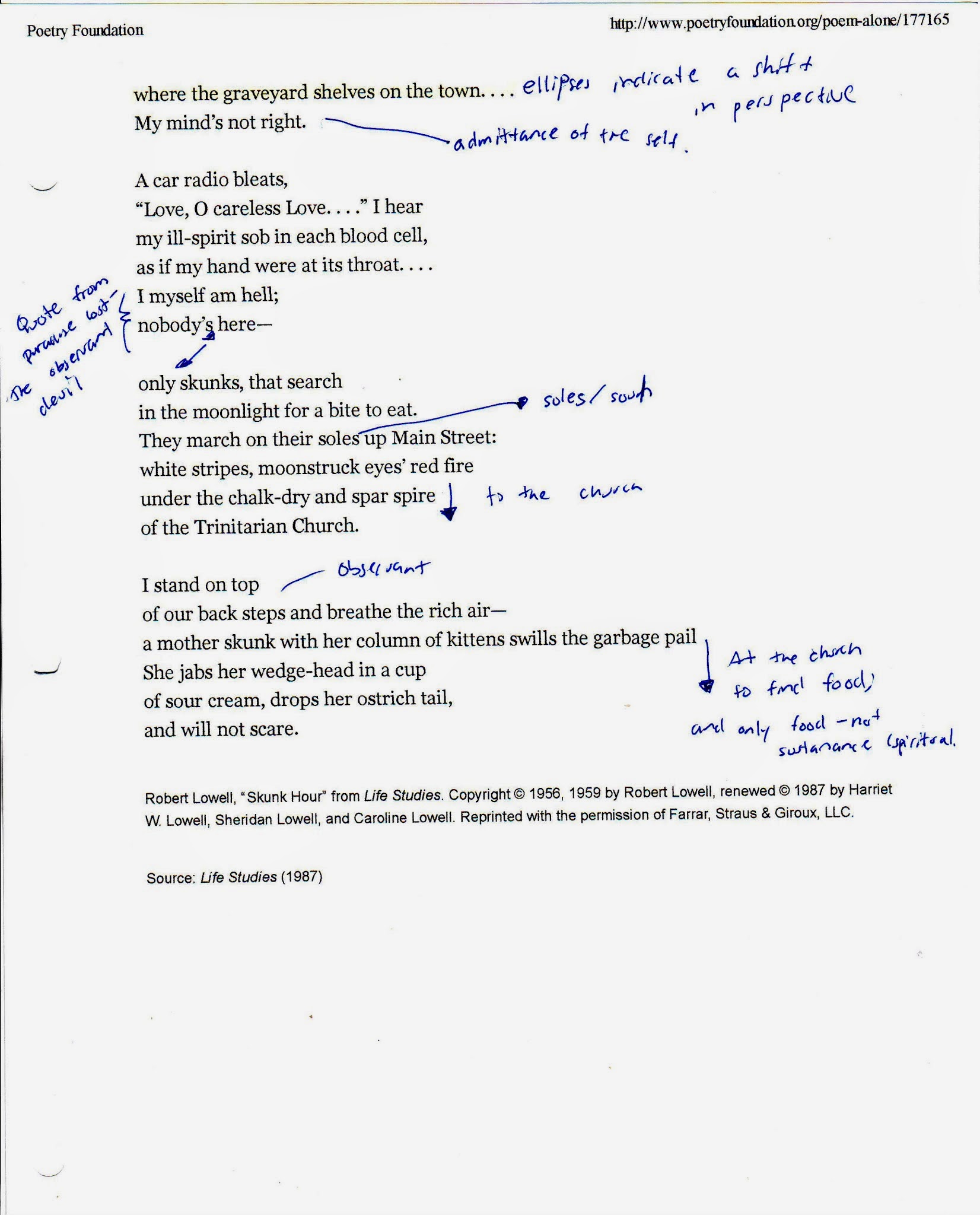

The beginning of the second half of the poem starts out with setting, "One dark night, / my Tudor Ford climbed the hill's skull;" note the usage of semi-colons throughout the poem and here the focus is the vehicle climbing on it's own up this hill (literal or metaphor whatever). Then the inclusion of the "I" speaker becoming prominent, "I watched for love-cars. Lights turned down / they lay together, hull to hull" A sense of connection that the speaker notes not only here but also with the first half -- here the cat's out of the bag. The speaker is the observer who continues to observe, "where the graveyard shelves on the town. . . ." then to himself, "My mind's not right."

"My mind's not right." Yep, this is the line that opened up poetry. So simple, right? There's probably similar things written everyday that is recognized as poetry. But the distinction here is the blurred line between persona and personal, and observation and acknowledgment. Was there lines like this in the mid twentieth century, absolutely. But this line, I feel, went against the whole formalist/observational approach. Here is the "raw" against the "cooked" (yes, read this article -- The Raw and the Cooked -- Robert Lowell's acceptance speech for his collection Life Studies in which this poem is in).

So from here on out the images seem more personal, "A car radio bleats, / 'Love, O careless Love. . . .' I hear" Note that the speaker is experiencing more at this point, "my ill-spirit sob in each blood cell" again pay attention to the double consonants or vowels here as though they: sticking together as the sound drowns out the other (with exception of blood) "as if my hand were at its throat. . . ."

Then the line that alludes to Paradise Lost, " I myself am hell; nobody's here" A little dramatic, but this is an admittance of how the speaker observes the self -- hell, why not? And with nobody here (person) the next image of the skunks become highly metaphorical.

The skunks search, "in the moonlight for a bite to eat. / They march on their soles up Main Street: / white stripes, moonstruck eyes' red fire." The further the actions are described, the more demonic they seem, but also with more purpose on location. "under the chalk-dry and spar spire / of the Trinitarian Church" is this line foreshadows a commentary on religion or perhaps the self, most likely.

It is the last stanza though where the metaphor of the skunks are given a solid purpose, but first the emphasis of observation from the speaker, "I stand on top / of our back steps and breath the rich air" then:

a mother skunk with her column of kittens swills the garbage pail

She jabs her wedge-head in a cup

of sour cream, drops her ostrich tail,

and will not scare.

Here's the important part here, "cup of sour cream." Seems innocuous, but that's what it supposed to do in the poem. Gone are the high allusion, the people of the past, the music that bleats -- this plain language is meant to ground the scene in a sense of the real.

Also note that the focus is on the "mother" (yeah, there's a slight Oedipal thing going on here if you really want to go into it) skunk who guides her kin to eat, just like how something big that sticks in the mind descends to smaller things, "will not scare." Either stands up for something good or bad. So the skunk could be a metaphor for a thought, that thing that makes the mind not right, linger like a smell, but then note the emotional pull behind it "scare" -- what can scare a lingering thought?

Originally read: September 19, 2013

More information about the Poet: Robert Lowell

Probably the most influential poem in the mid twentieth century. Overstatement, probably (I don't know the entire history of late 1950's - 1970's poetry -- well there's "Howl" which played more of a cultural impact...,but let me just continue). Most influential in that this style of writing, Confessionalism, was recognized by critics and academia which, in turn, opened up recognition of other poetry styles.

So this is why many students have to (begrudgingly) write essays about this poem specifically. And let's be honest, this poem is the anti-fun at least for the first half, and then confusing but momentum based in the last half. Yes, I wrote probably five essays on this poem during my academic career (all of paling in comparison with the five thousand other essays about this poem), and here is another one.

The one thing I note in the first half of the poem is the setting and location: somewhere in the north east, and sometime past summer. What the poem does in the beginning is start out in a third person mode -- more observation based, and more exposition based. There are three characters described in the first half: an heiress, a "summer millionaire," and a "fairy."

So the first is the heiress, "Nautilus Islands' hermit" who "lives through winter in her Spartan cottage;" note the semi-colon here to act an immediate comparison here, "her sheep still graze above the sea." Note how the sheep acts like a metaphor of distinction. Not drowning, but still "above all things" and yett, "she's in her dotage." Someone living alone.

So the following line sums up the first stanza, "Thirsting for / the hierarchic privacy / of Queen Victoria's century," the importance here is not the verb (thirst) but the time frame (Queen Victoria's century) and how privacy can be looked at as escapism.

The next three lines have a slight rhyme scheme, "she buys up all / the eyesores facing her shore, / and lets them fall" with "all" and "fall" -- this sense of a descent is on the surface, but the rhyme is also foreshadows the next person discussed, "the summer millionaire." (note the usage double -ll with the next stanza).

"The season's ill-- / we've lost our summer millionaire / who seemed to leap from an L.L. Bean" Yes, the last word is "catalogue" but I didn't want to exapnd my quotes. "Ill," "millionaire" and "L.L. Bean" all have the double -ll in it. Why? I don't know, but to me, this is the last vestige of hanging on to something similar -- even if it's the same letter drowned out sonically within itself. And of course the visual language shows a certain type person being described, "his nine-knot yawl / was auctioned off to lobstermen. / A red fox stain covers Blue Hill." -- what's left behind is picked up back someone lower (lobstermen).

The last description is toward "our fairy." Yes, the fairy could hit multiple references: a gay man, a whimsical person, or a figment (all can apply here) I think this stanza opens up for several types of criticism to be applied (Colonialism, Historicism, Deconstruction) -- whatever floats your boat. Just note that the focus of color "orange," " his fishnet's filled with orange cork, / orange, his cobbler's bench and awl;" bright, somewhat apparent colors, which hides intent, "there is no money in his work, / he'd rather marry."

This is the first half of the poem: people who are lost from the iconic to the prestigious to the lowly to the bright -- all of them lost internally in someway, but are remembered and are known externally. This concept will apply to the second half of the poem.

The beginning of the second half of the poem starts out with setting, "One dark night, / my Tudor Ford climbed the hill's skull;" note the usage of semi-colons throughout the poem and here the focus is the vehicle climbing on it's own up this hill (literal or metaphor whatever). Then the inclusion of the "I" speaker becoming prominent, "I watched for love-cars. Lights turned down / they lay together, hull to hull" A sense of connection that the speaker notes not only here but also with the first half -- here the cat's out of the bag. The speaker is the observer who continues to observe, "where the graveyard shelves on the town. . . ." then to himself, "My mind's not right."

"My mind's not right." Yep, this is the line that opened up poetry. So simple, right? There's probably similar things written everyday that is recognized as poetry. But the distinction here is the blurred line between persona and personal, and observation and acknowledgment. Was there lines like this in the mid twentieth century, absolutely. But this line, I feel, went against the whole formalist/observational approach. Here is the "raw" against the "cooked" (yes, read this article -- The Raw and the Cooked -- Robert Lowell's acceptance speech for his collection Life Studies in which this poem is in).

So from here on out the images seem more personal, "A car radio bleats, / 'Love, O careless Love. . . .' I hear" Note that the speaker is experiencing more at this point, "my ill-spirit sob in each blood cell" again pay attention to the double consonants or vowels here as though they: sticking together as the sound drowns out the other (with exception of blood) "as if my hand were at its throat. . . ."

Then the line that alludes to Paradise Lost, " I myself am hell; nobody's here" A little dramatic, but this is an admittance of how the speaker observes the self -- hell, why not? And with nobody here (person) the next image of the skunks become highly metaphorical.

The skunks search, "in the moonlight for a bite to eat. / They march on their soles up Main Street: / white stripes, moonstruck eyes' red fire." The further the actions are described, the more demonic they seem, but also with more purpose on location. "under the chalk-dry and spar spire / of the Trinitarian Church" is this line foreshadows a commentary on religion or perhaps the self, most likely.

It is the last stanza though where the metaphor of the skunks are given a solid purpose, but first the emphasis of observation from the speaker, "I stand on top / of our back steps and breath the rich air" then:

a mother skunk with her column of kittens swills the garbage pail

She jabs her wedge-head in a cup

of sour cream, drops her ostrich tail,

and will not scare.

Here's the important part here, "cup of sour cream." Seems innocuous, but that's what it supposed to do in the poem. Gone are the high allusion, the people of the past, the music that bleats -- this plain language is meant to ground the scene in a sense of the real.

Also note that the focus is on the "mother" (yeah, there's a slight Oedipal thing going on here if you really want to go into it) skunk who guides her kin to eat, just like how something big that sticks in the mind descends to smaller things, "will not scare." Either stands up for something good or bad. So the skunk could be a metaphor for a thought, that thing that makes the mind not right, linger like a smell, but then note the emotional pull behind it "scare" -- what can scare a lingering thought?

Comments

Post a Comment